Type a search + hit enter!

Nutritionally, there are three monosaccharides that make up all carbohydrates: glucose, fructose, and galactose. When glucose and galactose join together, they create lactose. Lactose is the main carbohydrate present in human milk, providing ~8.5 calories per ounce of human milk. Average lactose concentrations: are stable over the first 6 months of lactation decrease slightly from […]

read more

latest post

read more

Nutritionally, there are three monosaccharides that make up all carbohydrates: glucose, fructose, and galactose. When glucose and galactose join together, they create lactose. Lactose is the main carbohydrate present in human milk, providing ~8.5 calories per ounce of human milk. Average lactose concentrations:

-

are stable over the first 6 months of lactation

-

decrease slightly from 6 months-1 year and then remain stable over the second year of lactation

-

are higher if the infant is feeding frequently and lower if it has been a while since the infant has fed

Lactose is an interesting disaccharide, because infants are able to digest it due to the release of an enzyme called lactase. Lactase breaks the bond between glucose and galactose, both of which can be absorbed into the body. From birth, infants with galactosemia cannot consume lactose – not from breast milk or standard infant formula. Galactosemia is an inability to produce energy from galactose, and so levels in the blood rise. This can have severe consequences, including failure to thrive and death if not diagnosed.

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) are also carbohydrates, but they do not provide any caloric value to the infant. HMOs serve as a food source for beneficial bacteria and can also have a direct impact on the infant’s immune response.

From what we know about HMOs:

-

there are over 200 structures

-

mothers secrete a consistent profile of HMOs

-

different mothers secrete different types of HMOs

Human milk oligosaccharides can also be protective of viral and bacterial causes of diarrhea – depending on secretor status and Lewis antigen status of the HMOs produced.

Glycoconjugates are carbohydrates bound to protein or lipid molecules. These molecules are important for the infants innate immune response. A well known example of a glycoconjugate is lactoferrin – a molecule that serves as a bacteriocide and fungicide by hydrolyzing their RNA. Lactoferrin also serves as a stimulant to small intestine maturation in the newborn. Interestingly, lactoferrin has also been implicated in bone health in postmenopausal women, and more recent research is looking at the impact of lactoferrin on healthy infants.

The more I learn, the more I am convinced: human milk is magic.

Looking for more information about nutrition and lactation? Click below to download my 2 page resource on tips!

read more

As a nutritional biochemist by training, I absolutely love when my love of nutrition collides with my love of breastfeeding. For this reason, I was so excited when I found this study that looked at maternal consumption of a low FODMAP (fermentable oligo-, di- and mono-saccharides and polyols) diet on associated infant colic symptoms. What […]

read more

What you feed your baby and how it impacts their gut bacteria – scientifically termed the “microbiome” – has been a growing area of interest in the breastfeeding world. It is well established that feeding an infant cow’s milk based formula significantly changes the number of species and type of bacteria that grow in an infant’s gastrointestinal tract, and is associated with negative clinical outcomes. However, there is less research looking at the difference between receiving milk from the infant’s birth mother (termed “mother’s own milk”) or donor human milk.

Recently, a new article was published in American Journal of Clinical Nutrition that explored the differences between infants fed either donor human milk or their own mother’s milk.

What is donor human milk?

In the context of this research article, donor human milk is milk purchased from mothers who are producing too much. This milk is then screened and pasteurized (subjected to heat treatment) by Prolacta Bioscience in order to remove all bacteria. Pasteurization is important in this context because the donated milk is going mainly to premature infants who may be sick or immunocompromised. Milk banks want to ensure that there are no pathogenic bacteria or viruses that could hard these infants.

What difference does it make?

Donor human milk is different from milk that would come from an infant’s own mother for a few reasons.

-

Exposure to heat can decrease the concentration of certain micronutrients

-

Exposure to heat can decrease the activity of certain enzymes and immune compounds

-

The loss of bacteria does mean potentially harmful bacteria, but can also mean the loss of bacteria beneficial for development of the infant microbiome

What is the impact on the infant microbiome?

This new research provides evidence that infants fed a diet consisting mostly of donor human milk (average: 14% mother’s own milk) have a decreased diversity of gut microbiota in all stool samples collected over the 6-week duration of the trial.

The infant’s fed their mother’s own milk had more Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides genus bacteria than donor human milk fed infants. These bacterial species have been shown in other research to be beneficial for the growth and development of the infant when they are in the neonatal intensive care unit. Additionally, lower levels of Bacteroides bacteria have been linked to development of obesity in individuals with metabolic syndrome.

Donor human milk fed infants had more Staphylococcus genus bacteria. This genus of bacteria is known to contain pathogenic microbes. This could put the infant at an increased risk of development of illness.

Maybe most importantly, infants fed mostly their mother’s own milk (average: 91% mother’s own milk) had higher feeding tolerance than infants fed donor human milk. This is certainly important in growth and development, because the more food that the infant is tolerating, the faster they can grow.

Why is this important?

As much of my research focuses on the use of donor human milk, this article further emphasizes that donor human milk is supposed to be used specifically as a band-aid, with the goal of providing an infant their mother’s own milk. A mother’s milk is specifically designed to meet the needs of her infant. The mother’s milk contains immune components specific to that dyad’s environment, nutrition optimized for the infants age and status, enzymes to help that baby digest and absorb nutrients, and so much more. We need to do better at nurturing a culture that provides women the support and encouragement they need to feel empowered to breastfeed their baby.

read more

Over the past 10 years we have seen a rise in the number of states where marijuana sales and use are legal. This has opened the door for women to publicly ask about, and for researchers to publicly investigate marijuana use during lactation. There are properties of marijuana that raise concern about it’s use during […]

read more

Last week I posted a step-by-step guide to returning to work successfully when you have been breastfeeding – naturally we must now talk about how to safely store the breast milk that you pump.

Note: Always be sure to wash your hands prior to pumping or handling expressed breast milk.

How long can you store milk?

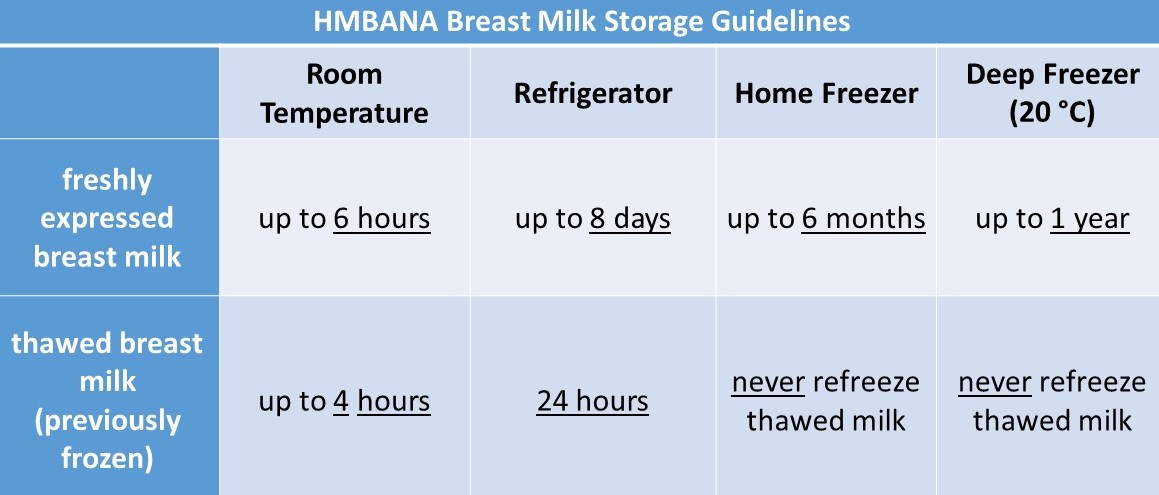

The Human Milk Banking Association of North America (HMBANA) has published guidelines for breast milk storage based on current evidence for limiting bacterial growth and retaining nutritional content of the milk. Room temperature would be classified as 75.2 °F.

Store your milk in volumes that your baby consumes in one feeding. For example, if your baby consumes 3-4 ounces per feeding, you can store your milk with 4 ounces per container.

To do this: After you are done pumping, combine warm milk into one storage container. If the container is not full, you can place it into the fridge so you can add more milk prior to freezing.

When you pump again later, combine the freshly expressed milk, cool it in the fridge, and add it to the storage container after it has cooled. Then, you can move your storage container to the freezer.

Note: Do not combine warm milk with cooled milk!

What type of container should I store my milk in?

When storing your expressed breast milk, any clean and sanitized container with a securely fastening lid will do. If you are choosing a plastic container, you will want to make sure that it is BPA free.

Popular milk storage containers include:

-

Clear, plastic, zip-seal storage containers

-

Clear, glass jar with a screw-top lid (think mason jar)

When you are moving your milk into a standing fridge or freezer for storage, you will want to store as far back into the fridge/freezer as the milk will go. The temperatures in the rear of the space are more stable than the temperatures near the doors. Additionally, less light reaches the milk in the rear of the space.

My dissertation research showed preliminary evidence that light exposure can impact the level of some vitamins in human milk – thus, you may want to consider a light-shielding container (Purity milk storage bags, amber or opaque glass containers, or clear containers wrapped in aluminum foil). You can also help protect your milk by pumping in low-light conditions when possible.

How often should I clean my pump parts?

The CDC has a nice infographic about breast pump maintenance that you can find here.

If you are using a single-user pump, you can store all of the pump parts that touch your skin or breast milk in the fridge and wash and sanitize those parts once per day.

Looking for an easy way to remember this information? Download my 2 page quick guide to hang on your fridge!

read more

It is no secret that the United States consistently under-performs in the area of maternal and child health. Offering paid leave to new parents is no exception. Many mothers across the U.S. are returning to work well before their child is 6 months old and it is very possible that breastfeeding is still not going […]

Get Your copy →

Cross the finish line with confidence.

Don't walk into your IBCLC exam nervous - with our comprehensive study guide in your back pocket, you'll be prepared for every scenario and question.